Between 20 October and 26 November 2014, the University of Portsmouth’s SPACE gallery will host ‘A Story of Revolutions’, an exhibition by Patrick Altes. Patrick Altes, a French artist born in Algeria, explores diaspora and identity in a body of work responding to a Leverhulme residency within the University of Portsmouth’s School of Languages and Area Studies, working with Dr. Natalya Vince. Themes include post colonialism, political manipulation and the dichotomy between oppressors and the oppressed.

The exhibition has already toured in Ireland, the UK and in Algeria – where Patrick was selected to participate in the Third Oran Biennale of Mediterranean Contemporary Art – and we are delighted to welcome the works ‘home’ to where it all began.

The exhibition is open on weekdays 9am-5pm and admission is free.

You are warmly invited to a ‘Meet the Artist’ event on Friday 14 November, 4-7pm at SPACE (Eldon Building West, Winston Churchill Avenue, Portsmouth PO1 2DJ) as well as a public talk given by Patrick on Tuesday 28 October at 4pm in Eldon North 0.20.

This exhibition is included in a series of events organised by the Faculty of Creative and Cultural Industries and the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Portsmouth as part of the Being Human festival, the UK’s first national festival of the humanities (15-23 November 2014).

In the following text, Patrick Altes and Dr. Natalya Vince discuss the residency.

A historian’s perspective…

Patrick Altes came to work in the School of Languages and Area Studies at the University of Portsmouth for ten months in 2012-13. He was funded by the Leverhulme Trust’s Artist in Residence scheme, which brings artists into academic departments that do not normally teach art. The aim of Patrick’s residency was for him to work collaboratively with staff and students, responding to the teaching and research which goes on in our department in order to produce a body of work which expresses academic ideas in new ways and for new audiences as well as his individual artistic concerns and interests.

For 132 years – between 1830 and 1962 – Algeria was a very distinctive part of the French empire. Strictly speaking, it was not a French colony, instead, it was considered an integral part of metropolitan (mainland) France with the Algerian provinces of Oran, Algiers and Constantine having the same status as French départements such as the Dordogne or Pas de Calais. Unlike other French colonies in Africa and Asia, Algeria also had a very large settler population. These settlers came from across the Mediterranean basin, and included people of Spanish, Italian and Maltese, as well as French, origin. In 1954, there were around one million ‘Europeans’ (settlers or people of settler origin) for 8.5 million ‘French Muslims’. ‘French Muslims’ was an official label to describe the autochthonous Muslim population – the term ‘Algerians’ was appropriated by settlers, in order to mark out their distinct identity from the French of metropolitan France.

Settler political, economic and social domination was entrenched through legal frameworks which excluded the autochthonous population from full citizenship rights. At the same time – and whilst never losing sight of the profound distinction between citizens of the French Republic and colonial subjects – elements of a shared culture could emerge, particularly in more socially mixed working-class urban areas. A small number of Europeans of Algeria also became committed anti-colonialists, and participated in the bloody, hard-fought, seven-and-a-half-year long War of Independence, which would eventually lead to Algerian independence in 1962. For Algerians, 1962 marked the birth of a state, and in some ways, the birth of a nation. For the settlers, it was the end of ‘French Algeria’. The vast majority of them, Patrick Altes and his parents included, fled the country, fearing rightly or wrongly that their only choice was ‘the suitcase or the coffin’.

In France, former Algerian settlers or ‘pieds noirs’ as they come to be known (literally: ‘black feet’) acquired – some might say cultivated – the image of an aggrieved group: both abandoned by the French state and victims of the new Algerian state. Academics working on post-colonial France and/or Algeria tend to be circumspect of the dominant pied-noir discourses which circulate notably on webpages and internet forums. At worst, these are angry, racist diatribes. At best, they are nostalgic recollections of a bygone era in which the dichotomy between coloniser and colonised is conveniently blurred in memories of couscous, mint tea, days at the beach under the Mediterranean sun and Muslim neighbours and employees who ‘we got on with fine’.

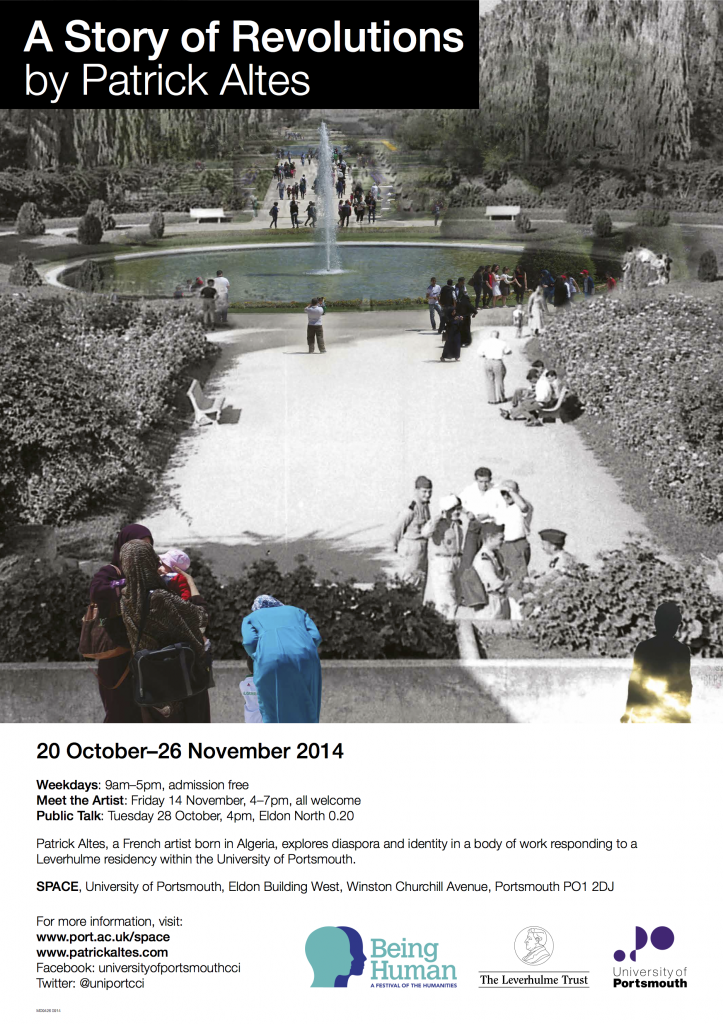

Patrick Altes’s brings a new perspective to this public debate. Through art, he succeeds in challenging both pied-noir nostalgia about ‘French Algeria’ and academic and popular preconceptions – and indeed misgivings – about what a pied-noir voice might represent. The works explore how Algerian pasts intersect with Algerian presents, but are pointedly un-nostalgic, freed from the tired tropes of longing for the past, or imagining how things might have worked out better or wistful dreams of reconciliation. The present and past are superimposed on each other without any facile suggestions that they are all neatly linked. Algerian and French (colonial) figures cohabit the space without trite implications that they are all one and the same. In short, Patrick Altes succeeds in exploring connections between people, cultures and spaces whilst never losing sight of the political and historical importance of recognising the distinction between coloniser and colonised, the difference between the past and the present and the distance as well as the proximity between the northern and southern shores of the Mediterranean.

The artist’s perspective…

This series of large-scale digital artworks was created by fusing old photographs of a forgotten and lost ‘pied noir’ world in Algeria prior to the expulsion of the French by the revolutionary Algerians in 1962, sourced from family photographic archives of French settlers, with my own contemporary images, sketches, objects, drawings and text and family photographic archives of Algerian people.

The transactional act of this request for photographs from someone’s private, personal history – and their selecting, handing them and giving me permission – is in fact a dynamic exchange in the now where they share their personal history with an artistic exploration that encompasses past, present and future.

This artistic ‘Truth and Reconciliation process’ is a personal attempt to shift perceptions and engage in an open-minded and creative dialogue to acknowledge the wounds of the past, the effects of the Algerian revolution but also the new relationship that is emerging after more than 180 years of strained cohabitation and to contribute to a different understanding between France and Algeria.

***

Zapruder, an Italian social and political magazine featured Patrick Altes’ ‘A Story of Revolutions’ series with ‘Pied Noir Cowboy’ as a cover in its Movimenti Nei Mediterraneo edition of April 2014 and JadMag, edited by Tadween Publishing, a subsidiary of the Arab Studies Institute (based in Washington and Beruit), featured “Garden of Eden” in a special issue of The Afterlives of the Algerian Revolution.