In this post, Dr. Natalya Vince considers the popular obsession with female fighters, both today and in the past, and examines the gulf that often exists between the image and the reality of women in uniform.

The role of Kurds in Iraq and Syria in fighting Islamic State (IS, alternatively known as ISIS, ISIL or Da‘ech) is currently a major focus in the international media. Particular attention has been paid to women fighters within the Kurdish forces. Last week, multinational retailer H&M was forced to issue an apology when an item from their autumn/winter 2014-15 collection – an olive green jumpsuit, styled with military boots and a high-waisted belt – was accused of tastelessly channelling ‘peshmerga style’ by imitating the kinds of outfits worn by female Kurdish soldiers. The Swedish fashion giant insisted that the similarities were purely coincidental – incidentally, the same claim of unfortunate coincidence was made (perhaps somewhat more convincingly) this August by the British sex toys and lingerie specialist Ann Summers, when they launched a new underwear range called ISIS.

Images from H&M and AFP, reproduced on Al Arabiya News.

Images from H&M and AFP, reproduced on Al Arabiya News.

Whilst we might find the incongruity of ISIS erotic underwear mildly amusing, it is not surprising that many found the implication that female soldiers were fashion muses deeply offensive. No reasoned academic argument could sum up quite why this is so offensive better than the British band Pulp in their 1995 hit ‘Common People’, a scathing social critique about rich kids pretending to be ‘common’ ‘because [they] think that poor is cool’. As frontman Jarvis Cocker put it, ‘Everybody hates a tourist, especially one who thinks it’s all such a laugh.’

An obsession of the image of the female fighter, however, is not the preserve of misguided fashionistas and other ‘tourists’. On the contrary, shots of uniformed and armed woman in the Kurdish forces have dominated much recent serious photojournalism from the region and have been published in broadsheet newspapers and exhibited in scholarly institutions. The website of the UK Guardian currently houses a slideshow of photographs of Kurdish women peshmerga by Maryam Ashrafi) and the Institut de Recherche et d’Etudes sur la Méditerranée et le Moyen-Orient in France (iReMMO) is currently hosting a photography exhibition by Yann Renoult on a similar theme. The gaze that both these photographers direct towards their subjects is a respectful one. The idea that these women represent the possibility of a new society in the region, championing greater gender equality, is an obvious overtone. Such representations are useful on the international stage for both Kurdish politicians seeking to reinforce Kurdish autonomy and/or move towards statehood and the Western coalition, which can at last claim to have a progressive partner in the region.

Using women to present a political movement as progressive and ‘modern’ is hardly new. During the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), the National Liberation Front (FLN) devoted significant energy to producing photographs and films of uniformed women bearing arms in the rural guerrilla (maquis) in order to counter French propaganda claims that the nationalist movement was a minority of reactionary religious fanatics. As FLN supporter Frantz Fanon famously put it in L’An V de la Révolution algérienne in 1959: ‘Algerian society reveals itself not to be the womanless society that had been so well described. Side by side with us, our sisters upset a little more the enemy’s plans of attack and definitively liquidate old myths.’

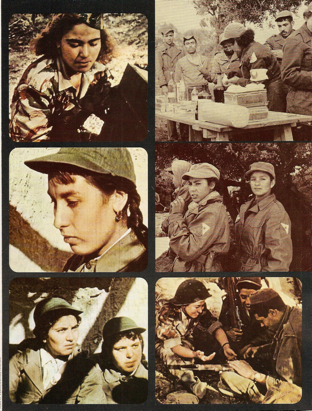

The images below showing Algerian maquisardes (women in the rural guerrilla), were taken by a team of FLN filmmakers and photographers, including René Vautier, who was a key figure in the creation of Algerian cinema and in the construction of the narrative of the nation conveyed through this cinema.

Images by Vautier/ Dalmas/ Tallandier, reproduced in Historia Magazine in 1972. The caption which accompanies the images reads: ‘Muslim women go up into the mountains. They are given auxiliary roles most of the time [such as] teachers [who] give Arabic lessons to [National Liberation Army, ALN] soldiers, nurses, social workers in neighbouring villages. A few take up arms.’

Studying these photographs is in itself interesting – but it doesn’t tell us very much about how these women experienced warfare. In 2006, I was fortunate enough to participate in a seminar series organised by Valérie Pouzol (expert on women and the Israel-Palestine conflict) and Fabrice Virgili (specialist on gender and Second World War France). Researchers working on women in armed movements in Algeria, France, Latin America, Palestine, Turkey, Chechnya and South Africa explored how women participated in the construction of gendered propaganda to advance their political causes, but also how women could find themselves constrained by the categories created by this propaganda, or living a parallel existence to a glorifying narrative which was completely disconnected from their daily lives.

One of the speakers was Olivier Grosjean, who spoke about gender and radicalism in Turkey and the place of women in the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK), based on interviews with former female activists and combatants. Some of the findings he talked about in his paper are in an article published in 2013 entitled ‘Théories et construction des rapports de genre dans la guérilla kurde de Turquie’. Without denying the very positive way in which many women talk about their time in the guerrilla and the vast diversity of experience (shaped by whether women were from rural or urban areas, their level of education and age amongst other factors) he concludes: ‘There is a clear gap between the idealised image of the “liberated” Kurdish female combatant and the reality of gender relations within the PKK guerrilla [my translation].’ This apparently obvious statement is often forgotten, and is worth underlining.

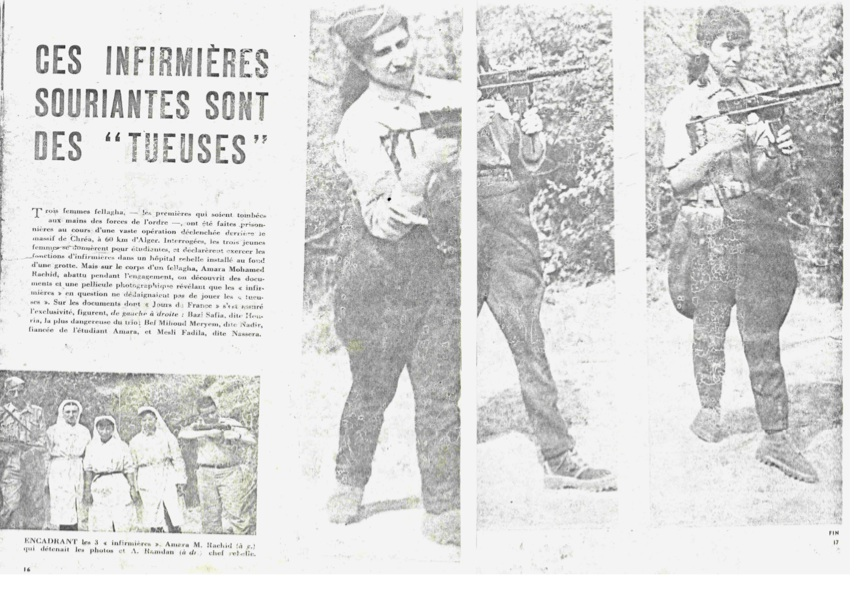

As well as exploring the gulf between image and reality, we also need to think about how women react to propaganda about them. In 2005, I interviewed Fadéla M., who as a trainee nurse was one of the first women to join the FLN’s rural guerrilla movement in 1956. She describes how the head of her maquis unit took a whole film of photographs of her and two other women. The purpose of the photos, she explained, was to show a forthcoming meeting of the United Nations that the FLN was not just a group of outlaws, as they were stigmatised by the French state and in the colonial press, but a whole people fighting for independence. In fact, the photographs came to serve another purpose. Shortly after they were taken, the three women and the roll of film were captured by the French army. Sensing the possibility of a propaganda coup, the army passed onto the French press a selection of images of the three women in uniform, brandishing guns. On 11 August 1956, the magazine Jours de France published the photographs under the headline, ‘These smiling nurses are “killers”.’

Jours de France, 11 August 1956

Jours de France, 11 August 1956

The choice of language sought to provoke shock at the way in which these women had transgressed their nurturing role as both women and nurses, highlighting the unsettling contrast between their youthful attractiveness and their violent acts, not to mention their profound ingratitude in turning the nursing skills provided by the French education system against the ‘motherland’. Fadéla describes how the colonial press (and indeed Le Canard enchaînée in metropolitan France) reported that they were Egyptian women as ‘they could not believe that Algerian women were taking to the maquis’. At the same time, Fadéla recounts, ‘Many people [men] joined the maquis when they saw these photos. They said to themselves, “how is it that women can fight and we are like ‘women’ – in inverted commas – staying at home?”’ Speaking many years later, Fadéla has critical distance from the ways in which other people sought to manipulate her image. She tells an empowering story by demonstrating her conscious manipulation of gendered stereotypes. But this is not the case for all female combatants and there are many different stories which go untold behind striking images of women in uniform.

An irony of sorts, given the long-standing popular interest in the image of the uniformed and armed female guerrilla, is that in irregular armies, women and men are rarely neatly kitted out in military attire. During the Algerian War of Independence, the French authorities placed extremely tight controls on the import, sale and circulation of military clothing (including that which was used or second-hand) which could be of use to the FLN. Indeed, the import or wholesale purchase of any shoes bigger than a size 40 (6½ UK size) were subject to inspection at the point of sale or customs officers (circumventing this restriction led to a thriving practice in falsely labelling shoe sizes). Maquisards and maquisardes were not only often poorly equipped, they were also often poorly dressed for cold weather and rough mountainous terrain. The good clothes, where there were any, were the ones used in the photos.

This unglamorous reality was no barrier to former FLN activist Yasmina, who became a high-end fashion entrepreneur in Algeria after independence. Her 1963 autumn/winter collection was pitched as traditional Algerian designs with a modern twist for ambassadors wives, and readers of the Algerian press were reminded that Yasmina had first found fame posing in a fashion magazine wearing leopard-print military uniform in 1962. (The exact set up of Yasmina’s business is not entirely clear from the materials I have, but its very existence is quite fascinating in the centralised, state-owned economy of socialist Algeria – Yasmina is interviewed on her shop premises in the 1968 documentary Les filles de la revolution.)

For a very different perspective on women in uniform, we might turn to Khadjidja B., another former maquisarde, for whom her uniform, and clothes in general, came to embody her difficulties of readapting to civilian life. Interviewed in 2005, she described her demobilisation in 1962: ‘I saw young women in town with nice haircuts and fashionably dressed. I was wearing a filthy uniform and shoes one size too big which hurt my feet [….] When I first started to travel [outside of Algeria], the first thing that I would buy was lots of underwear, bras and shoes! Things that I didn’t have in the maquis. I’d buy much more than I’d need like there would be no tomorrow.’ In this account, what appears to be frivolous consumerism is instead a poignant expression of the legacy of war.

***

For a selection of (free) teaching materials on women, psychological warfare and the Algerian War of Independence, including extracts of various primary documents translated into English, please see http://humbox.ac.uk/3777/