Republished from

Tom Harper

University of Surrey

Where once China sought communist revolution, it now seeks global economic expansion. As a result, the African continent has been one of the major areas of Chinese foreign economic investment. Numerous studies of China’s Africa policy have appeared in recent years, a number of which accuse China of exploiting resource rich African states or behaving like an imperial power in the continent, most notably Peter Hitchens’s assertion that China is building a ‘slave empire’ in Africa [1].

These views on Chinese policy also reflect the changes in the perceptions of China in the Western mind. The crude stereotypes of the Yellow Peril that dominated Western culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries have given way to a fear that China will follow in the West’s imperial footsteps. In other words, the legacy of imperialism underpins today’s perceptions of China’s foreign policy as well as Chinese identity.

Chinese engagement in Africa illuminates the influence of the imperial experience. The initial form of Chinese policy in Africa came as ideological and military assistance to the various anti-colonial movements of the 1950s in their struggles against the once dominant European empires that had been ravaged by the Second World War. During this period of decolonisation, Beijing formed strong ties with a number of African nations that would become increasingly important to Chinese economic goals once the Cold War subsided. Should these goals be seen as neo-imperialism?

Three Worlds Theory and Perceptions of Chinese Neo-Imperialism in Africa

The experience of European imperialism strengthened the ties between China and Africa. The major imperial powers of the 19th century victimised both, although the former was never formally colonised as a whole. Never the less, this experience was utilised by Beijing to achieve policy goals, as symbolised by the Three Worlds theory (三国理论), which advocated Chinese leadership of the Third World in opposition to the former colonial powers that made up the capitalist First World, on the basis that China had undergone the same experiences as much of the developing world, yet was uniquely placed to lead them [2]. This was largely abandoned at the end of the Cold War in favour of economic development, although it does reappear in China’s accusation of hypocrisy levelled at the Western powers over their claims that China’s approach to Africa resembles that of a neo-imperial power [3].

Western claims of Chinese neo-imperialism also illustrate the continued influence of the imperial experience. As Chinese engagement in Africa has spread, so has Western concerns over these policies. One of the most prominent of these claims is that Chinese policy is a form of neo-imperialism. Utilising language reminiscent of the indirect means of economic control depicted in works, such as Kwame Nkrumah’s Neo Imperialism (1965), there is a perception now shared among a number of African as well as Western writers that China will exploit the African states in the way of the European powers.

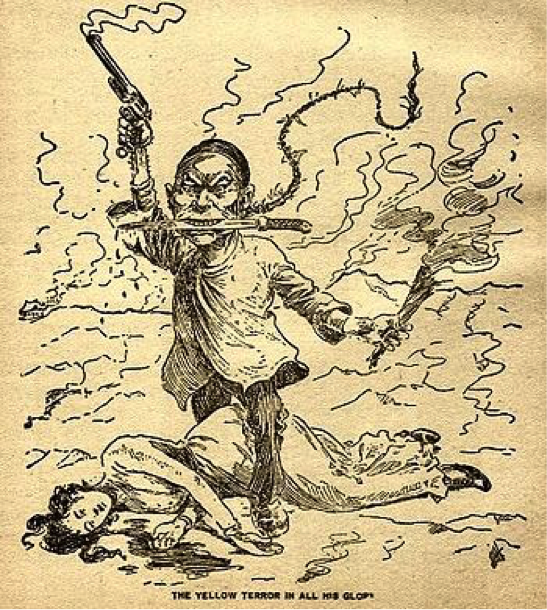

As with the perceptions of Chinese policy towards Africa, the Western image of China has also been a product of the imperial experience. Possibly the best known example of this is the phenomenon of the Yellow Peril as epitomised by Sax Rohmer’s nefarious Chinese mastermind, Fu Manchu. Rohmer’s novels were written against the time of China’s Century of Humiliation (百年国耻) where the European powers and later Japan preyed upon the floundering, corrupt Qing dynasty that had ruled the country from 1644 until the revolution of 1911. This was largely rooted in the Opium Wars of 1839 and 1856 as well as the anti-Western Boxer rebellion in 1899, both of which served to damage Qing China’s prestige and stability, which in turn is a stark contrast to the inscrutable menace that Rohmer and his contemporaries painted. Such perceptions portrayed China as the mysterious Orient, standing against everything that Western civilisation stood for.

If the Yellow Peril created an image of China rooted in the European imperial experience, its present image in Africa runs parallel with the decades of China’s rise to become one of the Great Powers of the 21st century. This assumes that with the changes in China’s status, fears over Chinese policy have changed from the Orientalism of the 19th century to the power politics of the 20th century, with the belief that China will ultimately challenge the established order and that such an aspiration will lead to increased tensions and even war [4]. However, China’s approach to Africa highlights the influence of the imperial experience on the perception of China and Chinese foreign policy.

If the previous perception of China was from a time when China was a victim of Western imperialism, the present image appears to be based on the assumption that China either already has or will become an imperial power in Africa.

China’s Financial Imperialism and Soft Power in Africa

This assumption is largely grounded in Beijing’s monopolistic economic policies in Africa. Chinese investment practices on the continent are eerily reminiscent of those utilised by the European empires of the past.

Firstly, a common claim is that Chinese loans for the development of African infrastructure serve an indirect means of control over the African states, an approach that the Western colonial powers had once used as a means of indirect rule over their colonial possessions.

Secondly, Chinese acquisition of African resources in exchange for Chinese products to Africa has led some critics to cry imperialism because of the perception that China’s African policies contains echoes of the old European empires.

A third element is the uptick in Chinese intervention in the continent. This has become particularly notable as Chinese interests come under attack, as shown by the assaults on Chinese oil interests in Sudan and the murder of Chinese nationals in Mali, both of which place pressure on Beijing to adopt a more proactive approach towards Africa [5]. Such a claim is reminiscent of the shift from informal to formal imperialism in the light of New Imperialism where colonialism was an expression of political and strategic rather than economic ambitions, as illustrated by the formal takeover of India from the British East India company in the light of the sepoy rebellion during the Indian Mutiny [6].

Conclusion

While China’s traditional culture, suppressed during the Maoist era, has made something of a comeback in recent years and has manifested itself in the perception of Chinese policy towards Africa. As opposed to the martial sources of authority that dominated Western imperialism, the Chinese system was based on the ideal of a ‘superior culture’ for others to follow. This can be seen in the revival of Chinese culture under the guise of cultural soft power (文化软力量) [7]. The most notable manifestation of this experience is the idea of China as a role model for economic development, as codified by the Beijing Consensus, which advocates a model of economic development without the need to adopt democratic norms [8]. This has gained a degree of traction in the developing world in the face of the perceived failings of the Washington Consensus to achieve economic development.

Traditionally, China’s imperial rulers sought to portray China as a cultural role model for other states to follow, most notably through the adoption of Chinese culture and writing system [9]. In recent years, this has largely come in the form of China as an example for developing states to emulate, as symbolised by the rise of the Beijing Consensus.

So, while the European imperial experience influences the perception of China’s African policies, China’s own imperial past is playing an important role, too. Whilst the formal European empires may have retreated from African colonialism, their legacy is reflected in the perceptions of Chinese engagement in Africa. This will continue to manifest itself so long as Beijing seeks to expand its political and economic interests in Africa. It remains to be seen whether China will in fact follow the path of the European imperial powers, or whether it will create a new form of imperialism.

Tom Harper is a doctoral student at the University of Surrey specialising in Chinese foreign policy. His current research focuses on the perspectives of Chinese engagement in Africa.

—————–

[1] Steven Hess and Richard Aidoo, Charting the Roots of Anti-Chinese Populism in Africa: A Comparison of Zambia and Ghana, Journal of Asian and African Studies, Vol.49 No. 129, May 2013

[2] Excerpts from Chinese Address to U.N. Session on Raw Materials, New York Times, 12th April 1974

[3] All-weather Friendship between China and Zimbabwe Beats the Slander, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Zimbabwe, 30th May, 2016

[4] Zackary Keck, US-China Rivalry More Dangerous than the Cold War, The Diplomat, 28th January 2014

[5] BBC News, Chinese peacekeeper among four killed in Mali attacks, June 2016

[6] Henri Brunschwig, French Colonialism, 1871-1914; Gallagher, Robinson, and Denny, Africa and the Victorians

[7] Yiwei Wang, Public Diplomacy and the Rise of Chinese Soft Power, Annals of the American Academy of Political Science, 616, March 2008

[8] Stefan Halper, The Beijing Consensus

[9] Feng Zhang, Chinese Hegemony