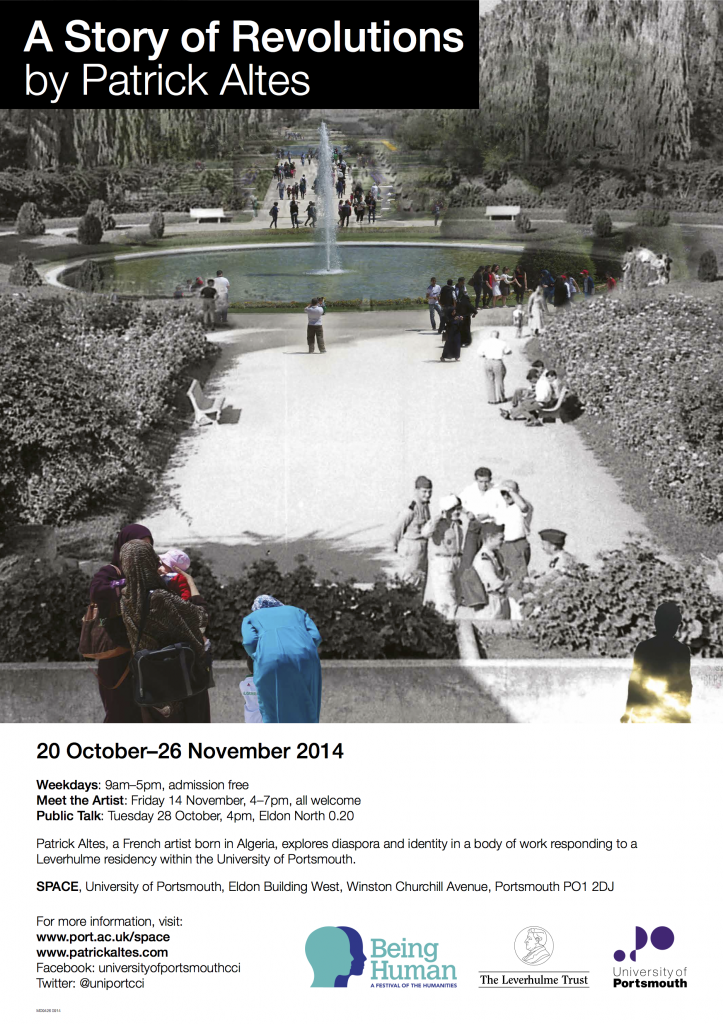

In this post, Fabienne Chamelot, a PhD student in the Francophone Africa cluster, interviews Patrick Altes. Patrick, a French artist born in Algeria, was a Leverhulme artist-in-residence in the School of Languages and Area Studies in 2012/13. An exhibition of his work, entitled ‘A Story of Revolutions’, was displayed at the University of Portsmouth’s SPACE gallery between 20 October and 26 November 2014, as part of the Being Human Festival.

How would you say your experience as an artist-in-residence in an academic context influenced your work, both in terms of techniques and the creative process?

Working with the University of Portsmouth, I had access to a lot of brainpower from experts in the field I was interested in. This was probably one of the key aspects, if not the most important one, during this residency. At the outset, some might have shown a few concerns about what a “pied noir artist” would produce, notably that I would bring up nostalgia in my work or highlight the “positive legacy” of French Algeria. However, these concerns were very quickly eliminated as I showed my interest in other ideas and worked from a very original perspective. Working with the University was very useful in defining more precisely the concept of each of my works before they actually started to materialise. Working with academics, I had to know what I wanted to say and I also had to find the means of saying it from the very beginning of a new piece, rather than, as it sometimes works, creating a piece on instinct and articulating its meaning at a later stage. It was quite an interesting and rewarding process for me in this respect.

In order to process this original concept, did you have working sessions with historians? How did these take place?

Not really. It took place with a lot of general discussions. In fact, I attended a lot of classes, took the course like almost any student, and took part in class discussions as well. Actually, I didn’t know much about French colonial history and the relationship between France and Algeria, mostly because of my past. For complex and various reasons, I had tried to avoid all of that. So when the residency started, I did not arrive with precise ideas in mind, but more as “Candide”, sharing my thoughts with Natalya Vince and other people I was working with in order to get their feedback all the way through the creation process. It was very helpful in order for me to elaborate mental images according to these conversations and, afterwards, to find a way to express and realise them. Being in touch with people who have academic knowledge and are not French – which I am – while literally discovering this part of history allowed me to remain detached from it, and comparison between the British colonial process and the French one helped me to get a lot of different ideas and to form an opinion that reflects in my work. From a superficial standpoint, things can appear obvious and simple: “oh, yes, colonialism is war and violence”; but very often these are just words. And when you take a deeper look into it, into the facts and dynamics of colonisation, then the evil borne by colonialism becomes clearer and real, the “beast comes to life”. As you get more intimate knowledge about how bad it was, these are not just words anymore. This is what fed my work.

Did you find the dialogue and working with scholars and students challenging or fulfilling? You probably didn’t feel the same at the beginning of the year as at the end?

I felt that people were welcoming and happy to listen to my ideas without any judgment. To be honest, I didn’t feel challenged at any time, but supported in a very positive and thorough way. Yet, this experience was tremendously important for my in many respects and I feel I am a different person now from who I was when I began the residency.

Do you fit in from the beginning? One might think that it would be very challenging to work as an artist in an academic environment?

That is true, but still, I did fit in because… well, it happened [laughs]. Actually, I didn’t really make any pieces whilst I was at the university, it was more a time of absorption. As this series focused on digital work, all the making had to be done outside the university. And I think it really helped, because I could separate the two environments and the two parts of the creation process as I explained earlier. On the one hand, I went to the university, where I could absorb notions, concepts, talk about ideas and so on, and on the other hand was my studio or, more precisely in that case, my office, as the pieces required hundreds of hours of computer work. During this process, I found it very helpful to go back and forth between the university and my office with one piece of work. Basically, I presented a first version of a work to people I worked with, discussed it with them, made changes, brought it back to them, and so on. So, in a way, it was quite an interactive process, and anyway constantly evolving. I also felt, as soon as I did my first piece, that I could not keep doing a similar piece again, in the same way that a series may work in painting when you create variations of an idea or concept. Because the setting was that of a university, each new piece could have been the first of a different series in a way. So I had to work on different ideas all the time while staying in the framework of post-colonialism, identity and representation.

How did you find the elements used in your artwork? Where did they come from and how did you select them?

I wasn’t much interested in using archival material but rather personal memories, especially pictures. I have to say that I faced certain difficulties in finding people who agreed to entrust me with their pictures. First, I tried to reach a few pieds noirs associations in this regard, but without any success. Then I located and contacted pieds noirs independently from associations, but I wasn’t very lucky with that either. So I tried through Facebook and joined a pieds noirs group and I found a few people who answered in a positive way to my request, and sent me pictures. I got a few pictures from my parents as well, 24 exactly, and then little by little a few more people agreed to work with me. I didn’t get hundreds of pictures but a few people did entrust their pictures to me, so I could use them in my work. It means a lot to me because it is not an easy thing to do, having something that belongs to your past and then allowing a perfect stranger to use it with the hope that the result won’t be offensive to your identity and experience. When introducing my work to them, I tried to explain its purpose while being as honest as possible. So far, I’ve shown the series to all the people who helped me and there hasn’t been any problem. Besides pictures from the pieds noirs community, I also got pictures from Algerian people who had some from the colonial time as well as from contemporary Algeria. And finally, I went to Algeria myself three times during this work and I took a lot of pictures. I also included some drawings and other photographs.

In most of the pieces exhibited, different techniques, colours and layouts are put together and arranged in order to create an aesthetic unity. But at the same time, each element keeps its own specificity and remains very distinct from the others. Would you say this is at the core of colonial encounter? That, in a sense, the specificity of this kind of encounter is that it never happened as such but created divisions and segregation between different peoples despite the fact that they lived together, shared a land and influenced each other in terms of culture?

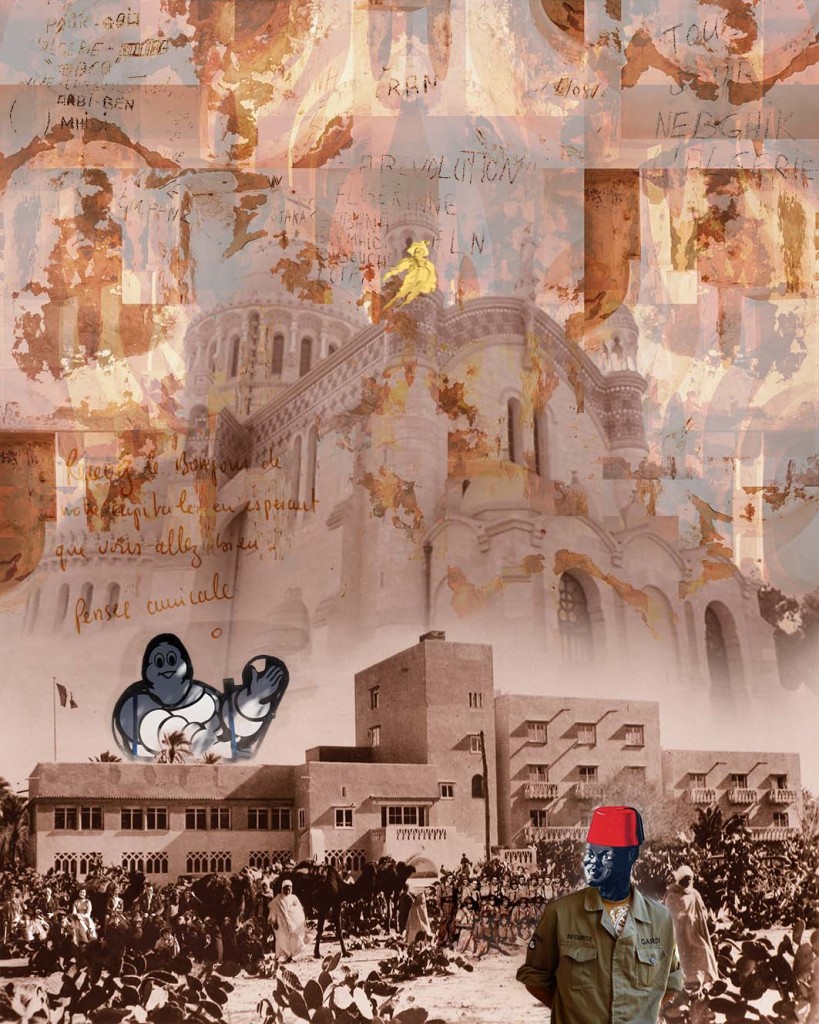

I think it’s true, and I did think about colonial encounter while working on this series, but I did not specifically create the artwork in order for it to reflect that reality. I rather approached it like a path towards better knowledge, and if I may say so, almost a spiritual knowledge. The work of Frantz Fanon has been very important in that regard and deeply impressed me, especially The Wretched of the Earth. Its influence over some of my pieces is actually very strong, like for example the Pied Noir Cowboy. In this piece, you can see a man riding a horse through what seems to be a wide empty space, and comic bubbles come out of his mind reflecting his thoughts. With a closer look, you’ll find that this apparently empty space he’s riding through is actually full of caricatures of people, of a mass. This is a reflection of Fanon’s work explaining that the colonists viewed Algerians as some primitive animal-like kind of people, always deviant and ready to organise an attack against them. They felt under constant threat from them and yet, at the same time, they also described Algeria as an empty country ready to be inhabited with no harm. And I have tried to recreate these two notions: on the one hand, the so-called “emptiness” of French Algeria according to the colonists, and on the other hand, surrounding the “cowboy”, the beast-like native Algerians ready to bounce on him. I think it is probably the harshest picture against colonialism in the series.

Pied Noir Cowboy

Pied Noir Cowboy

One could probably say the same kind of things about memories of colonisation nowadays and the stereotypes that they bear. Would you say that it is something specific to a period or that it is something enduring through times?

Very ironically, the same stereotypes described by Fanon were used by French people living in France against the pieds noirs when they arrived in France after the liberation of 1962. They were thought of as animals driven by their instincts and not completely human. It is very interesting to observe this shift from one group to another. In that respect, I would say it has endured.

The elements of your artworks match one to another with a very striking specificity, where they are both fragmented and fused. It reflects very well the confusion between identity and culture in a colonial, and later on, postcolonial context. How did you come up with this technique and idea? Was it something fully rational and well thought out, or did it “naturally” emerge at some point in your work?

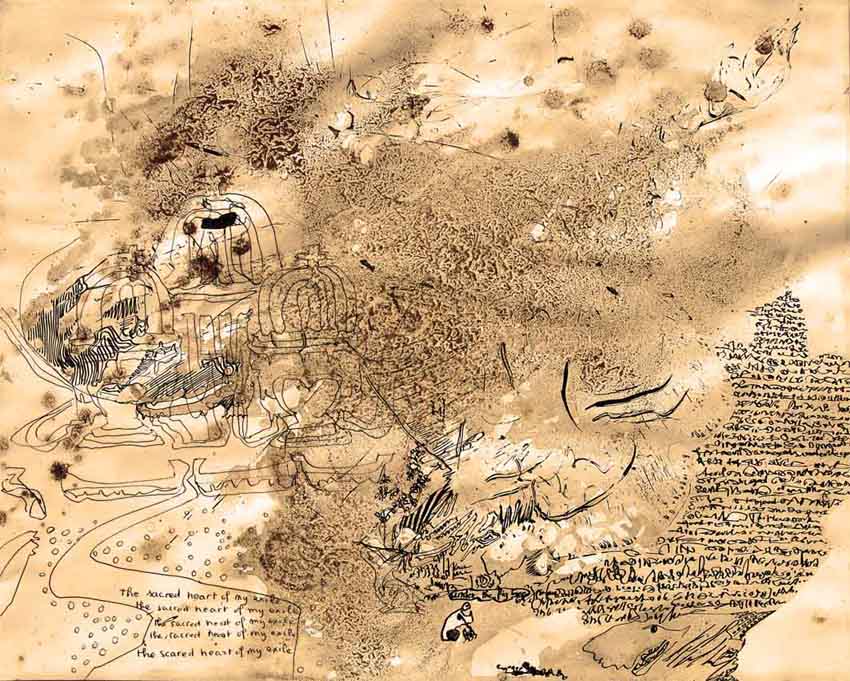

In the case of my work, nothing is ever rational! As an artist in France, I was not using computers at all. I discovered what great tools computers were when I did my MA in fine arts in Brighton in 2006-2008 and also when I got my first Mac. I then started to work with Photoshop and found that it echoed my own painting technique. In my work, I’ve always been interested in creating a sense of depth through additions and subtractions of layers. For instance, you can see it in the paintings of the series that they are made of different layers, and the closer you get to the role canvas, the deeper you are “into” the painting. The layers actually help to create closeness with the painting. Photoshop technique is based on piled up layers, partially covered or erased, which is somehow similar to the technique I’ve developed in my paintings. So I did develop a concept with this series but I did not create it from scratch. The emergence of deep layered detail is something that very well corresponded to what I wanted to do, so I enhanced and elaborated on this technique.

While doing this, were you focusing on the images or also analysing them from an intellectual point of view?

My unconscious is very active when I do this type of work and I rely on a process very much inspired by surrealism. I figure out correspondence between different elements and try a few combinations. Sometimes it doesn’t make any sense or it isn’t satisfying, so I let it go and try again later with different associations, until something begins to take shape in a way or another and that a “relevant concept” emerges from it. From there, I can start working on adding other elements and layers in order to qualify it or to enhance it until I’m satisfied with it. But it can take time and it is not necessarily a straightforward process. All my pieces are made of three elements: the concept I’m interested in sharing, the way I want to express it, and the aesthetic of the whole; it has to be pleasant to look at, to the extent it is possible. All of these are equally important and it can take time and a lot of attempts and fails to get there. In this series, I played with Orientalist aesthetics as well as Pieds noirs’ one, which is supposedly gaudy. In that sense, I could say that I added a layer of irony even though it is very real at the same time. In fact, I’ve tried to add as many “meaning layers of meaning” as possible. Sometimes it matched immediately and sometimes it appeared and was shaped as the work was executed.

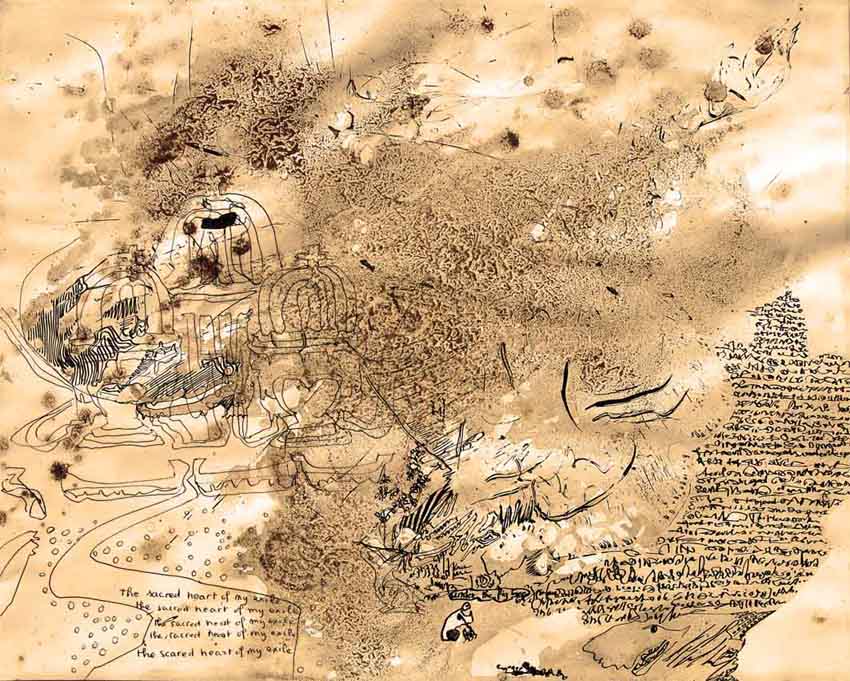

The sacred heart of my exile web

The sacred heart of my exile web

How would you say that the artist’s sight shapes the way he/she describes things? In history, as a scientific discipline, there is a methodological framework that defines the way investigation should be done and the way reflections should be communicated in order to remain objective. In art, on the contrary, one should explore his/her subjectivity in order to reflect a reality that transcends individuality. How would you say these two approaches can be combined or work together? It might have been something you experienced during your residency.

I wasn’t interested in applying or trying to adapt an academic approach to my work, nor to create something to which scholars only could immediately relate to because it would have consisted in a description of something rather than a work of art. In order for art to get there, it has to evade some realities and, at the same time, create a certain ambiguity in such way that people can input their own ideas, their own prejudice and their own vision in it, and do so to the extent that it would transform the work. When I’ve shown some of my pieces to people, their interpretation was not related at all to what I wanted to stress, but it doesn’t really matter after all. And I think that a piece of art becomes really interesting, almost an icon even, when people watching it can relate to it by being moved with a specific emotion without necessarily being able to explain it. That’s what I try to achieve, even though one can’t always succeed in that respect.

How would you define this series compared to the others you have created? Where would you say it stands in your personal and artistic trajectory?

This is my second residency with the Leverhulme Trust, which is something quite unusual in itself. The first one was about cancer and I had cancer so it was quite close to me but I did not engage in it in the same way. For some reason, I kept distant from it, maybe because I was scared of the whole thing. Still, it was a fulfilling work and it helped me evolve. But this series is very specific, it is the one I have most engaged with so far in terms of emotions and as an individual; I’ve opened up a lot in it. I would say it is definitely my best work so far and it includes the paintings as well as the digital works. In many different stages in the making of this series, I felt like I had a muse on my shoulder, which is not something I always experience in my work. For instance, the “P’tit gars bien de chez nous” is very powerful in my opinion, I’m very proud of it. And the same goes for the “Garden of Eden”. People might think there is a trick in the way the layers were piled up, but there is not. I went to Algiers, took some pictures of the Jardin d’Essai and when I came back, a person who had given me some pictures previously sent me a few more of them, including three old ones from the Jardin d’Essai, and the perspective was roughly the same as the one I had taken. It was amazing, and I started to work on this basis. And even though it looks like an easy picture, I put a lot of work into it as it was actually very difficult to achieve, and there was some kind of serendipity as well. I’m definitely very proud of it.

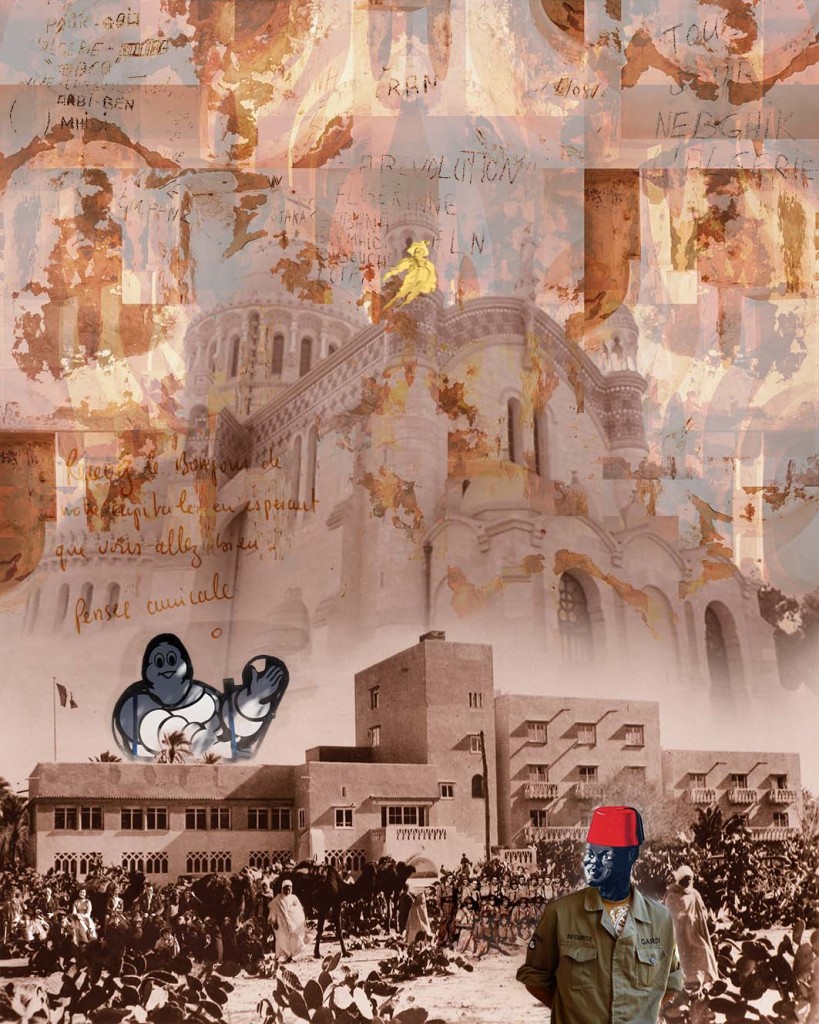

P’tit gars bien de chez nous

P’tit gars bien de chez nous

This exhibition has toured in different places. How diverse was the public receptions to your exhibition from one place to another?

It first went to Cork and I was really pleased to observe that people somehow related to it by transposing the experience of France and Algeria to the experience of England and Ireland. They felt a definite connection, which probably means that this series bears a kind of universality, which helps people connect with it. It then was showed in Chester where it was also very well received. Another exhibition happened in Algeria, which I am very happy about. It was part of the Biennale events in Oran last June and obviously some people were very moved by it, and by the fact that a French pied noir was coming back to Algeria presenting a work that was not pro-French and probably a little pro-Algerian – but not completely – with a heartfelt approach. So I think there were good reactions there as well.

What is your next project if you already have one in mind?

I probably won’t keep working on Algeria because then I would become the specialist of the question artistically speaking, which I don’t want to be, but I’m really interested in the concept of hybridity. I wouldn’t mind being able to gather threads of my experience in South Africa under the apartheid with the years I’ve spent in South America, where the concept of colonisation, first by the Spanish people and then by the United States, even though it is more of an economic fact, is quite alive as well. I like this notion of “in-between” and I am trying to work on it. I also appreciated working within academia and universities because they are such good assets for an artist, and hopefully it will happen again.