In this post, Prof Tony Chafer reports on his recent research trip in Benin and some of the challenges and opportunities available there for scholars working on French West Africa.

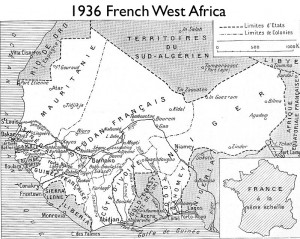

Having worked on decolonisation in former French West Africa for many years, Alex Keese and I wondered why no one, in the many studies we have read, has used the Benin archives. We knew of academics who had used the Senegal national archives, those of Mali, Mauritania and – to a lesser extent – Côte d’Ivoire, but no one, it seemed, had used the Benin archives. Yet Dahomey (modern Benin) had once been described as the Latin quarter of Africa, because of the number of French-educated Africans trained there, and graduates from its schools were to be found working for the colonial administration throughout French West Africa. The territory’s importance for any study of decolonisation in West Africa was thus beyond doubt.

Initial prospects for the visit did not look good. There was no sign of the national archives on the internet and it was only when I stumbled across a local press article on the web, reporting on the events that had been organised that week to mark the centenary of the creation of the archives, that I was reassured that they actually existed. The article even gave the name of the director, whose email address was easy to find on the internet as it was an unusual name. Unfortunately, the email bounced back. However, a further email to the chef du service de communication, who was also named in the article, yielded a response within the hour. We were welcome to visit and they had a number of series that would be of interest.

The visa necessitated a visit to an industrial estate in north London. But it was worth the journey just to meet the consul himself, who had been in the post since the country gained its independence in 1960. He was quite a character and had many stories to tell; I could have spent much of the day listening to them if I had not had further appointments to get to. In all the years he had been consul, he assured me, I was the first person he had come across to go to Benin for historical research. The prospects for doing some original research were by now looking much better.

I arrived in Benin three weeks later to discover a country that, compared to other countries in the region that I have visited, seemed on the surface to be noticeably poorer. Many unpaved roads in the country’s capital city, Cotonou, motor bikes rather than cars for taxis, petrol sold from bottles at roadside stalls rather than at petrol stations, were just some of the striking first impressions.

We arrived at the archives the next day and were welcomed warmly. There were more staff than readers in the airy reading room and we were immediately provided with detailed répertoires for the colonial period. Ordering files was straightforward and they arrived promptly. Here, clearly, was an unmined source for the colonial historian. We were interested in the period of transition from the colonial to the post-colonial period, so we mainly wanted to see political files – ‘political’ in the broadest sense, so including police, justice, labour and internal security files – from the mid-1950s to the 1970s. Unfortunately, there was virtually nothing in the archives for this period. The untapped mine of information covered the colonial period from the mid-1890s to the early 1950s, but then largely dried up.

Clearly, we needed to look elsewhere. We thought that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs might be a useful source of documentation on continuities in the relationship between the newly-independent Dahomey and the former colonial power, France. The chef du service de communication also helpfully suggested that the archives of the Assemblée Nationale might be a useful source. So we tried the Ministry of Foreign Affairs while she phoned her colleague at the National Assembly. At the Ministry the reply was: we have nothing before 1994-5. Apparently no one had ever requested documents for this period! The chef du service de communication at the National Archives told us that the staff there were relatively new, so offered to phone her colleague, who had been there for many years but had recently been transferred to another service, to see if he knew anything about the missing archives. He didn’t. It seems that the ministry has changed buildings at least once since independence, so we speculated that perhaps the archives had been left behind in a previous building. They are now looking for the missing thirty-five years. At the National Assembly the story was uncannily similar: the staff there had not seen any archives from before the mid-1990s. Documents on the first thirty-five years of Benin’s national history are hard to come by, it seems, at least in Benin itself. We have contacted but not yet heard from the Préfecture in Porto Novo and are still waiting to find out if the Présidence has any archives for the period.

So, if you are thinking of doing research on the colonial period in French West Africa, the Benin national archives are a great untapped resource – up to the mid-1950s. The staff are helpful and the working conditions are good. With the national archives of Senegal, which have been the staple for historians working on French colonialism in West Africa for many years, currently closed sine die, the Benin archives could provide a useful alternative resource.