Le corps retrouvé samedi dans le parc national de la Pendjari, au Bénin, où deux touristes français ont disparu mercredi, est bien celui de leur guide, a annoncé dimanche 5 mai à l’AFP une source proche du gouvernement béninois.

« Le corps du guide a pu être formellement identifié » bien qu’il soit « très abîmé » et « défiguré », a ajouté cette source, précisant qu’une grande incertitude régnait toujours quant au sort des deux touristes, dont la thèse d’un enlèvement se précise.

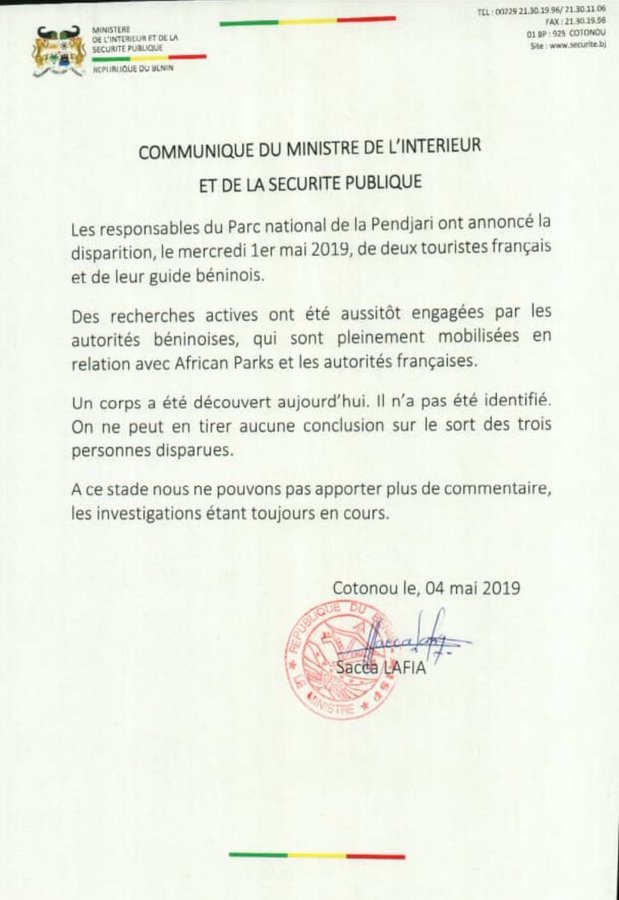

« Les responsables du parc national de la Pendjari ont annoncé la disparition, le mercredi 1er mai, de deux touristes français et de leur guide béninois », avait déclaré le ministère de l’intérieur béninois dans un communiqué publié samedi soir sur Twitter.Voir l’image sur Twitter

Gouvernement du Bénin✔@gouvbenin

Communiqué du Ministre de l’intérieur et de la sécurité publique relatif à la découverte d’un corps dans la partie septentrionale du #Bénin2920:45 – 4 mai 201933 personnes parlent à ce sujetInformations sur les Publicités Twitter et confidentialité

Un îlot de stabilité menacé

Le parc national de la Pendjari, dans le nord du Bénin, se situe près de la frontière avec le Burkina Faso, confronté à une dégradation alarmante de la situation sécuritaire sur son sol. Le Bénin est considéré comme un îlot de stabilité en Afrique de l’Ouest, une région mouvementée, où opèrent de nombreux groupes djihadistes liés à Al-Qaida et l’Etat islamique.

Read more on Le Monde Afrique